More Information

Submitted: January 06, 2026 | Approved: January 23, 2026 | Published: January 26, 2026

How to cite this article: Uppal R, Saeed U, Uppal SR, Amin H, Uppal MR. NAD⁺ Biology in Ageing and Chronic Disease: Mechanisms and Evidence across Skin, Fertility, Osteoarthritis, Hearing and Vision Loss, Gut Health, Cardiovascular–Hepatic Metabolism, Neurological Disorders, and Muscle. Ann Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2026; 10(1): 001-009. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.acem.1001032.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acem.1001032

Copyright License: © 2026 Uppal R, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: NAD⁺; Nicotinamide riboside; Nicotinamide mononucleotide; Sirtuins; PARP; CD38; Inflammation; Oxidative stress; Hepatic steatosis; Neurodegeneration; Muscle health

NAD⁺ Biology in Ageing and Chronic Disease: Mechanisms and Evidence across Skin, Fertility, Osteoarthritis, Hearing and Vision Loss, Gut Health, Cardiovascular–Hepatic Metabolism, Neurological Disorders, and Muscle

Rizwan Uppal1, Umar Saeed, Sara Rizwan Uppal3, Humza Amin3 and Muhammad Rehan Uppal1

1Islamabad Aesthetic Clinic (IAC) and Islamabad Diagnostic Center (IDC), Islamabad, Pakistan

2International Center of Medical Sciences Research (ICMSR), Islamabad, Pakistan

3ICMSR, Austin, TX, USA, ICMSR, Essex, United Kingdom

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Umar Saeed, Islamabad Aesthetic Clinic (IAC) and Islamabad Diagnostic Center (IDC), Islamabad, Pakistan, Email: [email protected]

Background: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺) is a pivotal coenzyme and signaling substrate that integrates redox balance with mitochondrial energy production, DNA repair, epigenetic control, and cellular stress resilience. Declines in NAD⁺ availability—frequently observed with ageing, chronic inflammation, and metabolic stress—have intensified interest in NAD⁺ restoration as a potential strategy to influence disease biology across multiple organ systems.

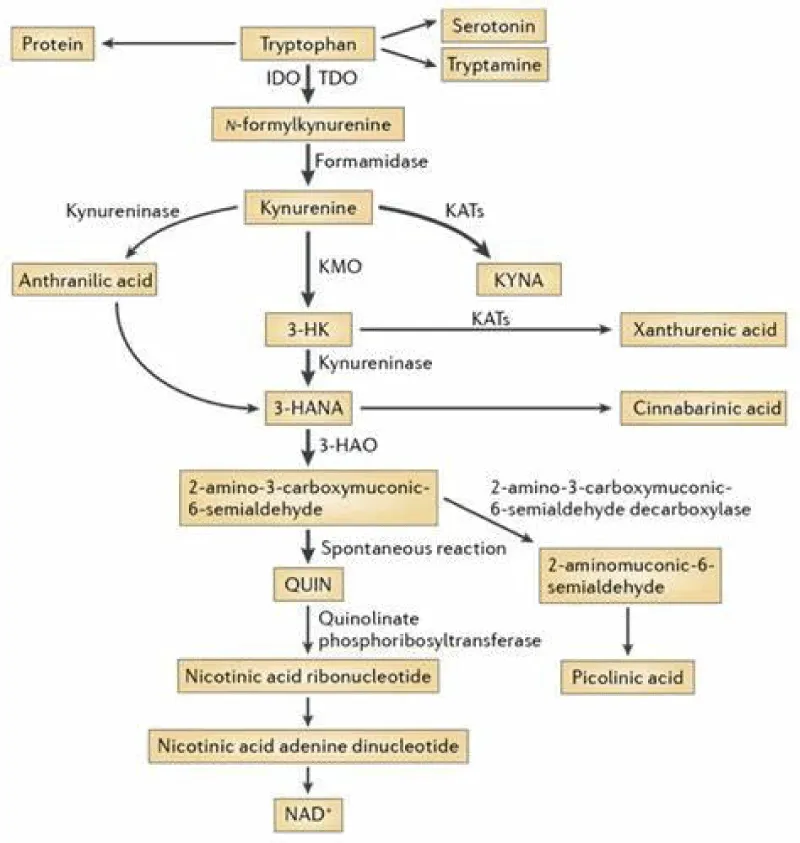

Objective: This narrative review summarizes contemporary mechanistic and translational evidence on NAD⁺ biosynthesis and turnover, highlighting the de novo kynurenine pathway and vitamin B3–dependent salvage routes (nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, nicotinamide riboside, and nicotinamide mononucleotide). We also examine how major NAD⁺ consumers and sensors, sirtuins, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and CD38 link NAD⁺ status to inflammation, oxidative stress, and tissue dysfunction in diverse clinical contexts.

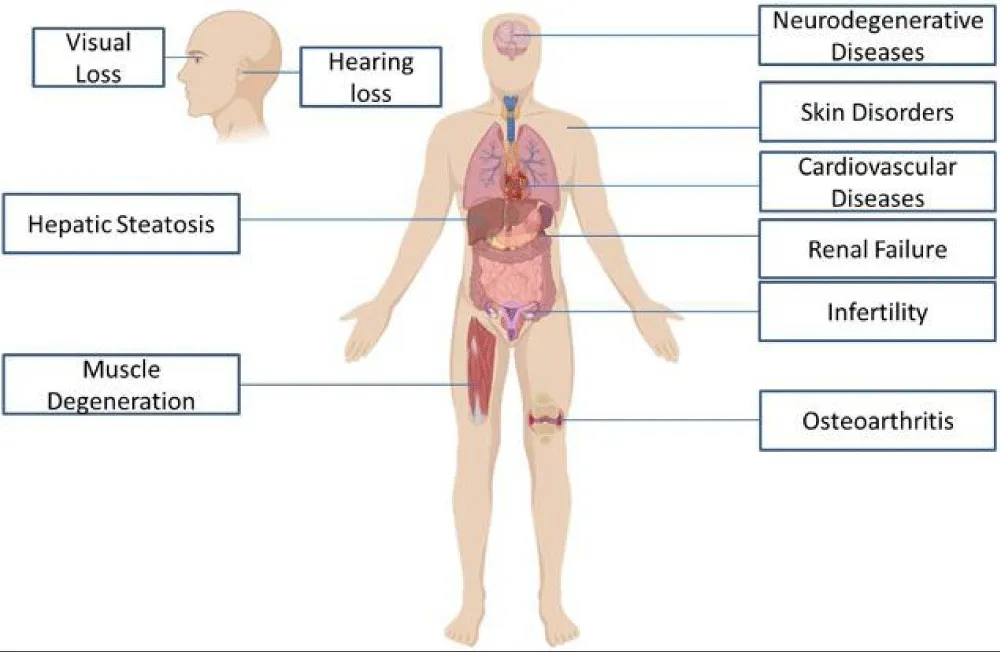

Methods: Peer-reviewed literature on NAD⁺ metabolism, NAD⁺-dependent signaling, and preclinical/clinical studies of NAD⁺ precursors was evaluated and organized into: (i) core biochemical functions in cellular energetics, (ii) NAD⁺ consumption in genome maintenance and immune signaling, and (iii) organ-focused evidence relevant to skin disorders, infertility and reproductive health, osteoarthritis, hearing loss, vision decline, gut barrier dysfunction, cardiovascular and renal metabolism, hepatic steatosis, neurological diseases, and skeletal muscle health.

Results: NAD⁺ supports glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, while acting as an essential substrate for PARP-driven DNA repair and sirtuin-mediated deacylation programs that shape mitochondrial fitness, inflammatory tone, and metabolic flexibility. Across experimental models, impaired NAD⁺ homeostasis repeatedly associates with mitochondrial dysfunction, heightened oxidative injury, and dysregulated immune–barrier responses, features shared by intestinal inflammation, neurodegeneration and ischemic injury, cardiometabolic disease, kidney injury, and fatty liver disease. Supplementation with NAD⁺ precursors (notably NR and NMN) reliably elevates NAD⁺ in preclinical systems and increases circulating NAD⁺ metabolites in humans, with early signals of pathway engagement; however, clinical outcomes remain heterogeneous across populations, dosing regimens, and endpoints. Evidence for intravenous NAD⁺ “drip” therapy is comparatively limited and insufficiently standardized, with constraints related to tolerability, dose consistency, and cost, underscoring the need for controlled trials.

Conclusion: NAD⁺ occupies a central position at the interface of energy metabolism, genome integrity, and immunometabolic signaling, providing a coherent framework for understanding how cellular stress can propagate multisystem dysfunction. Although NAD⁺-boosting strategies are biologically plausible and mechanistically supported, definitive clinical benefit across skin, fertility, osteoarthritis, sensory decline, gut disorders, cardiovascular and hepatic disease, neurological conditions, and muscle health will require well-designed human studies with standardized biomarkers, safety surveillance, and clinically meaningful endpoints.

The de novo synthesis of NAD+ primarily depends on the kynurenine pathway (KP), although NAD+ can also be recycled from nicotinic acid (NA), nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinamide riboside (NR). In mammals, NAD (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide) + is synthesized from either tryptophan or other vitamin B3 intermediates that act as NAD+ precursors [1]. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that cannot be produced by the human body and must be obtained through your diet, primarily from animal or plant-based protein sources. Discovered in the early 1900s after isolation from casein, a protein found in milk, its molecular structure was determined shortly after. Tryptophan, despite being the least concentrated amino acid in the body, plays a crucial role in various metabolic functions impacting mood, cognition, and behavior. Tryptophan elimination experiments have demonstrated its beneficial influence on mood, depression, learning, memory skills, visual cognition, and aggression control [2].

L-Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that cannot be synthesized by humans. It can be found in various foods. Whole milk is one of the richest sources of tryptophan, containing 732 milligrams per quart. 2% reduced-fat milk is also a good source, with 551 milligrams per quart. Canned tuna contains 472 milligrams per ounce, and while turkey is commonly associated with tryptophan, it’s not the highest source. Light meat contains 410 milligrams per pound (raw), and dark meat contains 303 milligrams per pound. Chicken is another good source, with light meat containing 238 milligrams per pound, and dark meat containing 256 milligrams per pound. Prepared oatmeal provides a good source of tryptophan with 147 milligrams per cup. Tryptophan is crucial for the production of serotonin, a mood stabilizer, melatonin for regulating sleep patterns, niacin (vitamin B-3), and nicotinamide [3,4]. Although not as abundant as in meat and dairy, cheddar cheese contains 91 milligrams of tryptophan per ounce, while peanuts contain 65 milligrams per ounce. Whole wheat bread contains up to 19 milligrams per slice, and refined white bread contains 22 milligrams per slice. Finally, chocolate can contain up to 18 milligrams of tryptophan per ounce [5]. Age-related mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to decreased NAD levels. NAD is critical for mitochondrial function, and as mitochondria become less efficient with age, NAD utilization can increase. Additionally, diet and lifestyle factors, such as poor nutrition, excessive alcohol consumption, and a lack of exercise, can accelerate the decline in NAD levels with age [6].

NAD⁺ IV (intravenous) therapy, also known as NAD⁺ drip therapy, involves injecting NAD⁺ (dissolved in fluid) into an individual’s vein to raise the concentration of NAD⁺ in the bloodstream, allowing them to receive the therapeutic benefits of NAD⁺ [7]. Due to potential side effects such as headaches and shortness of breath experienced by some individuals during therapy, IV NAD⁺ is often administered slowly, sometimes measured in drops (hence the term “drip” therapy).

Genetic factors can also influence NAD metabolism, with some individuals having genetic variants that affect their ability to maintain NAD levels with age. Certain medications, like those used to lower cholesterol (nicotinamide riboside), may impact NAD levels [8,9]. Scientists have explored the benefits of NAD supplementation and other interventions to counteract age-related NAD decline, including the use of precursors like nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) to boost NAD levels. However, it is essential to note that the effectiveness and safety of such interventions are areas of ongoing research and may not be fully established.

In contrast, many studies indicate that NAD⁺ precursors, particularly NMN, have anti-aging benefits, such as improving insulin sensitivity, enhancing physical performance and sleep, and increasing muscle strength. Therefore, there is more compelling evidence supporting the mitigation of aging in humans through NAD⁺ precursors than through NAD⁺ Drip IV therapy, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: NAD+ improves Human health in several distinct ways.

NAD roles in oxidation-reduction reactions

NAD works as a coenzyme in various cellular processes, primarily participating in redox (oxidation-reduction) reactions. Its primary function is to act as an electron carrier, shuttling electrons and protons between different molecules. NAD+ functions as an oxidizing agent, accepting electrons to become NADH [10]. NADH can then donate these electrons to other molecules, a transfer crucial for maintaining the balance of electrons in various cellular reactions to ensure their efficiency. NAD+ and NADH participate in the electron transport chain, a component of cellular respiration. In this chain, NADH donates electrons to complex I, initiating a series of redox reactions that culminate in ATP production. In glycolysis, NAD+ accepts electrons from glucose, converting it into NADH. In the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle), NAD+ is integral to the oxidation of acetyl-CoA, generating NADH. In the electron transport chain, NADH donates electrons to the chain, facilitating a proton gradient and ATP synthesis [11,12].

NAD+ effects on reducing DNA damage

NAD+ is also consumed during DNA repair processes, serving as a substrate for enzymes such as PARP (poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase) [13]. NAD+ is intimately tied to the activity of enzymes called PARPs (Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases) and CD38 (Cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase) [14]. PARPs are instrumental in DNA repair, ensuring the maintenance of genomic integrity, while CD38 is implicated in calcium signaling and immune regulation. These functions highlight the far-reaching implications of NAD+ in maintaining cellular health and resilience [13,14].

NAD+ effects for the prevention of hepatic Steatosis

NAD+ plays a crucial role in various liver detoxification pathways, particularly in the conversion of ethanol (alcohol) into acetaldehyde and acetaldehyde into acetate [15]. Additionally, NAD+ is involved in regulating immune responses, influencing inflammation and immune cell function. The balance between NAD+ and NADH is vital for maintaining cellular homeostasis, with disruptions affecting numerous cellular functions and processes. NAD is an irreplaceable component of cellular life, acting as a coenzyme that adeptly accepts and donates electrons, playing a central role in energy metabolism [16]. It is involved in glycolysis, the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle), and the electron transport chain, all critical processes for generating ATP. Moreover, NAD is essential for DNA repair mechanisms, with enzymes like PARPs facilitating DNA damage repair by consuming NAD. NAD+ is a versatile electron shuttle in redox reactions, maintaining the delicate balance between NAD+ (the oxidized form) and NADH (the reduced form), which is pivotal for cellular homeostasis. NAD+ is a central coenzyme involved in various fundamental cellular processes, making it indispensable for maintaining cellular energy, genomic integrity, redox balance, and overall cellular well-being [17]. NAD+ is involved in the regulation of enzymes that promote fatty acid oxidation in the liver. Fatty acid oxidation is the process by which the liver breaks down fats for energy. Adequate NAD+ levels are necessary for the efficient oxidation of fatty acids. NAD+ is a key player in maintaining the balance of reducing and oxidizing reactions within the liver. Hepatic steatosis can be associated with oxidative stress, which can contribute to liver damage. NAD+ participates in antioxidant pathways and helps protect liver cells from oxidative damage. NAD+ is associated with the regulation of inflammation. Inflammation in the liver is often linked to hepatic steatosis and its progression to more severe conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Modulating inflammation through NAD+ pathways may help reduce the impact of hepatic steatosis.

NAD+ effects on the eye

The development of age-related cataracts is a complex process influenced by various factors, including genetic predisposition, oxidative stress, and cumulative damage to lens proteins [18]. Studies have suggested that maintaining NAD+ levels may help protect against age-related eye diseases, including cataracts. Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body’s ability to neutralize them [19]. NAD+ is involved in the production of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) that help neutralize ROS and reduce oxidative damage to cells, including those in the eye lens [20]. Age-related declines in NAD+ levels may reduce the body’s ability to combat oxidative stress, increasing the risk of cataract formation. NAD+ plays a role in protecting against oxidative stress, which is a key factor in the development of cataracts.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a complex eye disease that affects the macula, a part of the retina that is responsible for sharp central vision [21]. AMD is influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors, and while there is no cure for the condition, various strategies aim to reduce the risk or slow its progression. The potential role of NAD+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide) in maintaining eye health and its link to AMD is an area of interest, but still being researched.

NMN treatment has shown modulation of ocular inflammation, oxidative stress, and complex metabolic dysregulation in murine models for eye diseases such as ischemic retinopathy, corneal defects, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration [22,23]. Chronic inflammation may contribute to AMD. NAD+ is involved in modulating the inflammatory responses of immune cells, potentially influencing the risk and progression of AMD. As with any health-related intervention, it’s essential to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen, especially for medical conditions like AMD. They can provide guidance and monitor your progress to determine the most appropriate approach to address your specific needs and health goals [24].

NAD+ effects on Gut

NAD+ precursors play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the gut barrier [25]. A deficiency in NAD+ has been associated with enhanced gut inflammation and leakage, as well as dysbiosis [26]. Conversely, NAD+-increasing therapies may offer protection against intestinal inflammation in experimental conditions and human patients. Accumulating evidence suggests that these favorable effects could be mediated, at least in part, by concurrent changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota [27].

NAD+ impacts on Neurological manifestation

Neuroinflammation and neuroimmunology-associated disorders, including ischemic stroke and neurodegenerative diseases, frequently lead to severe neurological function deficits such as bradypragia, hemiplegia, aphasia, and cognitive impairment [28]. The pathological mechanisms underlying these conditions are not entirely clear. SIRT2, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, has been shown to play a critical and paradoxical role in regulating ischemic stroke and neurodegenerative diseases [29].

NAD+ effects on Parkinson’s disease

While a few studies suggest that NAD⁺ Drip IV therapy may alleviate alcohol and drug addiction, as well as Parkinson’s disease, no studies have examined its effects on aging [30]. Oral administration of NAD⁺-boosting therapy is considered safer, more cost-effective, and consistently dosed compared to intravenous administration. Of the IV NAD⁺ studies mentioned, only those related to Parkinson’s disease show potential anti-aging effects. This connection is drawn from the fact that Parkinson’s disease onset typically occurs around the age of 60, making it an age-related condition [31].

NAD+ effects on kidneys

Kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs) have high energy demand, and disruption of their energy homeostasis has been linked to the progression of kidney disease [32]. Consequently, metabolic reprogramming of PTECs is gaining interest as a therapeutic tool. Preclinical and clinical evidence is emerging that NAD+ homeostasis, crucial for PTECs’ oxidative metabolism, is impaired in chronic kidney disease (CKD), and administration of dietary NAD+ precursors could have a prophylactic role against age-related kidney disease [33].

NAD+ effects towards heart

Sirtuin3 (SIRT3) is a member of the NAD+-dependent Sirtuin family located in mitochondria and can participate in mitochondrial physiological functions through the deacetylation of metabolic and respiratory enzymes in mitochondria [34]. As the center of energy metabolism, mitochondria are involved in many physiological processes, and maintaining stable metabolic and physiological functions of the heart depends on normal mitochondrial function. The damage or loss of SIRT3 can lead to various cardiovascular diseases. SIRT3 and NAD interplay is critical for processes, including gene expression regulation, DNA repair, and mitochondrial maintenance [35].

NAD+ effects on genetic modulations

NAD further extends its influence to modulate gene expression. NAD serves as a co-substrate for sirtuins, a class of proteins known for their regulatory role in cellular processes, including those implicated in cellular longevity, metabolism, and stress response [36]. In the context of cellular respiration, NAD interfaces with the electron transport chain, expediting the transfer of electrons to molecular oxygen. This vital electron flow results in the generation of a proton gradient and, consequently, the synthesis of ATP [37]. Beyond its role in aging and antiviral defense, NAD has a substantial impact on various facets of human health, and it plays an essential role in maintaining cellular metabolism. Serving as a co-substrate for enzymes involved in glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, NAD fuels the processes that generate energy for our cells [38].

NAD+ effects on detoxification

NAD also plays a role in detoxification pathways, acting as a key participant in the transformation of toxic agents, such as ethanol, into less harmful derivatives [39].

NAD+ effects on hair follicle cells

NAD does not directly repair hair loss; it may indirectly support hair health. Hair loss is a complex issue influenced by various genetic, hormonal, environmental, and lifestyle factors. NAD is crucial for the energy metabolism of hair follicle cells, and healthy hair growth requires an adequate energy supply to fuel the cells responsible for hair production [40]. Ensuring optimal NAD levels may indirectly support the energy needs of hair follicles [41]. Additionally, DNA damage in hair follicle cells can contribute to hair loss, so maintaining NAD levels may help ensure the integrity of the DNA in these cells. Chronic inflammation can play a role in hair loss conditions such as alopecia areata. Modulating inflammation through factors like NAD may have a beneficial effect in some cases [42].

NAD+ effects on skin disorders

NAD+ is essential for DNA repair processes within skin cells. When skin cells are exposed to various stressors, such as UV radiation from the sun, they can sustain DNA damage. Adequate NAD+ levels are necessary for efficient DNA repair, which can help prevent mutations that could lead to skin disorders, including skin cancer. NAD+ contributes to the maintenance of the skin’s barrier function. A healthy skin barrier helps prevent moisture loss and protects against environmental factors, which can reduce the risk of skin disorders like eczema or atopic dermatitis. Some skin conditions, such as psoriasis or rosacea, involve inflammation. NAD+ has been implicated in modulating inflammatory responses, which may influence the severity and progression of inflammatory skin disorders. Some skin disorders, such as premature aging or wrinkling, may benefit from NAD+ supplementation due to its involvement in cellular repair mechanisms and its capacity to support overall skin health. NAD+ may play a role in protecting skin cells from the harmful effects of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Sun exposure can lead to NAD+ depletion, and maintaining NAD+ levels might help mitigate the damage caused by UV radiation. NAD+ has been linked to the promotion of wound healing. It can accelerate the regeneration of skin cells, which is crucial in healing skin injuries and preventing complications that might lead to various skin disorders.

NAD+ role against infertility

Infertility is a complex issue influenced by various factors, including genetics, hormonal balance, environmental factors, lifestyle, and underlying medical conditions. While NAD+ plays important roles in these areas, it is not a guaranteed treatment for infertility, and its influence on fertility is generally indirect. Medical professionals may explore the use of NAD+ or NAD+ precursors as part of a comprehensive fertility treatment plan when there is evidence of NAD+ deficiency or cellular dysfunction. In women, NAD+ may be important for the health of the ovaries, regulation of the menstrual cycle, and overall reproductive function. Some studies suggest that NAD+ precursors, like nicotinamide riboside (NR) or nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), may support ovarian function. In men, NAD+ may affect sperm quality. Sperm require energy for their motility, and NAD+ is a key player in cellular energy production. Proper energy levels may support healthy sperm motility.

NAD roles against osteoarthritis

NAD+ itself is not a direct treatment for osteoarthritis; maintaining optimal NAD+ levels and supporting its functions may help mitigate some of the factors contributing to the development and progression of osteoarthritis. Healthy and efficient mitochondria are crucial for maintaining the integrity of joint tissues. Impaired mitochondrial function can lead to increased oxidative stress and tissue damage, contributing to osteoarthritis. Sirtuins may play a role in protecting joint tissues and preventing cartilage degeneration. Activating sirtuins through NAD+ supplementation or other means could potentially have a protective effect on joint health. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of osteoarthritis. NAD+ can influence inflammation through various pathways, including the regulation of immune responses. Controlling inflammation may help reduce the pain and damage associated with osteoarthritis. Joint tissues can be subject to DNA damage due to factors like oxidative stress and mechanical wear and tear. Efficient DNA repair processes may contribute to maintaining the integrity of joint tissues.

NAD effects to prevent hearing loss

Increased oxidative stress, resulting from factors like noise exposure and aging, can damage auditory hair cells and lead to hearing loss. NAD+ is involved in antioxidant pathways that help mitigate oxidative damage. DNA damage can occur in auditory hair cells due to various stressors. Efficient DNA repair can help maintain the integrity of the cells and prevent age-related hearing loss. The auditory hair cells in the inner ear require substantial amounts of energy to function properly. Maintaining optimal NAD+ levels can support the energy needs of these cells and help sustain their function. Healthy mitochondrial function is critical for maintaining auditory hair cell function. NAD+ is essential for the proper function of mitochondria, which are the powerhouses of the cell. Efficient mitochondrial function helps protect auditory hair cells from damage and oxidative stress.

NAD effects against muscle degeneration

Skeletal muscles use fatty acid oxidation as an energy source during prolonged physical activity. NAD+ plays a role in regulating enzymes involved in fatty acid metabolism. This process is crucial for endurance and preventing muscle fatigue. NAD+ serves as a coenzyme for sirtuins, a class of proteins that are involved in various cellular processes, including gene regulation, metabolic homeostasis, and cellular stress responses. Sirtuins, such as SIRT1 and SIRT3, play a role in maintaining muscle health, promoting muscle regeneration, and protecting against muscle atrophy. The role of NAD+ in muscle health is an area of ongoing research, and the specific mechanisms are still being elucidated. The application of NAD+ supplementation or interventions in the context of muscle degeneration may require further investigation.

What are Sirtuins and why is NAD critical for them?

Sirtuins are a family of NAD+-dependent enzymes that play a pivotal role in cellular regulation and various biological processes. These enzymes are involved in controlling gene expression, cellular metabolism, DNA repair, and stress responses [43]. The connection between sirtuins and NAD is crucial because sirtuins require NAD+ as a cofactor to carry out their enzymatic activities. Sirtuins require NAD+ to function. When NAD+ binds to a sirtuin enzyme, it undergoes a reaction that results in the removal of an acetyl group from certain protein substrates. This deacetylation process modifies the activity of these proteins and can have wide-ranging effects on cellular processes [44]. Sirtuins play a role in regulating gene expression by deacetylating histones—proteins that help package DNA into chromatin. Histone deacetylation can lead to a more compact chromatin structure, potentially silencing or activating specific genes. This process is associated with epigenetic regulation, where changes in gene expression occur without alterations in the DNA sequence [45].

Sirtuins are involved in regulating cellular metabolism, including processes like glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial function. For example, one well-known sirtuin, SIRT1, is implicated in promoting fat mobilization, improving insulin sensitivity, and enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis. Sirtuins play a role in DNA repair by influencing the activity of enzymes involved in DNA damage response and repair mechanisms. This helps maintain genomic stability and integrity. Sirtuins are linked to cellular stress responses and can help cells adapt to various stressors, such as oxidative stress or nutrient deprivation. By regulating key pathways, sirtuins contribute to cellular resilience and survival [46].

Research into sirtuins has garnered significant attention due to their potential role in extending lifespan and promoting healthspan (the period of life spent in good health). Some studies have suggested that sirtuins, particularly SIRT1, may influence aging-related processes through their effects on metabolism, cellular stress responses, and DNA repair. Activation of sirtuins has been associated with the benefits of caloric restriction, a dietary intervention known to extend lifespan in various organisms. Certain compounds, often referred to as caloric restriction mimetics (such as resveratrol), are thought to activate sirtuins and mimic some of the effects of caloric restriction [47].

Sirtuins are activated by NAD and resveratrol

In addition to NAD+ precursors, resveratrol is another compound that has received attention for its potential to activate sirtuins [48]. Resveratrol is a natural polyphenol found in various foods, including red grapes, red wine, and berries. It has been studied as a potential activator of SIRT1, with some research suggesting that resveratrol may enhance the activity of SIRT1 and provide benefits associated with caloric restriction and longevity. While there is evidence from laboratory studies and animal research suggesting that resveratrol may have health benefits, including potential effects on aging, it’s important to note that the translation of these findings to human health is an ongoing area of investigation [49]. The effects of resveratrol on human aging are still not entirely clear, and more research is needed to establish its potential benefits and safety in humans. Additionally, the benefits of resveratrol are likely to be influenced by factors such as dosage, the form of resveratrol used, and individual variations in response [50]. The interaction between resveratrol, NAD+, and sirtuins in the context of human aging is complex and continues to be a subject of scientific exploration. While there is promising evidence from preclinical studies, more research is needed to determine the full extent of resveratrol’s effects on aging and whether it can be harnessed for therapeutic purposes in humans [51].

Interplay of Sirtuins and NAD for cell longevity

Sirtuins use NAD as a co-substrate and are involved in various cellular processes, including hair growth regulation, although this is an area of ongoing investigation [50]. High levels of stress can contribute to hair loss, and NAD is involved in managing stress and oxidative stress within cells. Maintaining a healthy NAD balance may help mitigate the damaging effects of chronic stress [51]. Within the intricate web of biological processes, the dynamic interplay between NAD and Sirtuins stands out as a pivotal axis with profound implications for aging mechanisms, viral replication prevention, and human health regulation. NAD+ further acts as a substrate for enzymes known as sirtuins, which play a role in gene regulation. Sirtuins use NAD+ to deacetylate proteins, influencing gene expression, cellular processes, and longevity [52,53].

Aging, that inevitable journey from youth to old age, is a subject of enduring scientific fascination. At its core, NAD+ takes center stage. This coenzyme is pivotal in cellular energy production, serving as an essential player in the electron transport chain during oxidative phosphorylation [29]. However, as we age, NAD+ levels tend to decline, potentially triggering a cascade of deleterious effects. This decline in NAD+ is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and impaired gene regulation [30]. These proteins, particularly SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT3, rely on NAD+ for activation and play a paramount role in addressing age-related challenges [54]. By orchestrating these vital functions, Sirtuins contribute to preserving cellular health and retarding the onset of age-related diseases. Consequently, the partnership between NAD+ and Sirtuins offers a promising avenue for interventions aimed at mitigating the effects of aging, potentially allowing us to enjoy healthier and more vibrant lives [55].

Antiviral effects of NAD+ dependent Sirtuins

Beyond the scope of aging, NAD+ and Sirtuins also emerge as guardians against the intrusion of viral pathogens. Viruses, cunning invaders, rely on host cell machinery for replication, often evading the immune system’s watchful eye [56]. Here, Sirtuins play a critical role. Activated by NAD+, these proteins exert control over various cellular processes. They inhibit viral gene expression, impeding the ability of viruses to replicate within host cells [57]. Moreover, Sirtuins bolster the host’s antiviral immune responses, providing a double layer of defense against viral intrusion. This intricate partnership forms an essential line of defense against viral pandemics and emerging pathogens, underscoring the vital role NAD+ and Sirtuins play in safeguarding human health on a global scale [56].

Effects of NAD+ dependent Sirtuin Isoform 2 on Hepatitis B Virus replication

SIRT2 is a member of the sirtuin family, which are NAD+-dependent deacetylases. These enzymes can deacetylate histones and regulate chromatin structure. Alterations in chromatin structure can impact the accessibility of the HBV genome to the host transcription machinery, potentially affecting viral gene expression and replication [57]. SIRT2 can modulate the activity of various transcription factors through deacetylation. It is conceivable that SIRT2 may influence the activity of transcription factors involved in regulating HBV gene expression, such as HNF4α (Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 alpha), which is known to play a role in HBV replication [58].

SIRT2 plays a role in cellular metabolism and energy homeostasis. HBV replication is closely associated with the metabolic state of host hepatocytes. SIRT2 may indirectly impact HBV replication by altering cellular metabolism in infected cells [59]. SIRT2 interacts with various cellular proteins. SIRT2 may interact with host proteins involved in antiviral responses or cellular defense mechanisms, which could influence the outcome of HBV infection. SIRT2 is involved in DNA repair and maintenance of genomic stability.

HBV replication can introduce mutations and DNA damage in host cell DNA [60]. SIRT2 may play a role in responding to and repairing such DNA damage, potentially affecting the persistence of viral DNA in the host genome. NAD is a cofactor required for the enzymatic activity of sirtuins, including SIRT2. Adequate levels of NAD are crucial for sirtuin function. In conditions of cellular stress or metabolic changes, NAD levels can fluctuate, potentially affecting sirtuin activity and, indirectly, viral replication. Some viruses, including HBV, have been shown to alter host cell metabolism, which can impact NAD levels.

Changes in NAD availability could, in turn, affect sirtuin activity and the regulation of viral replication [59]. NAD levels may also influence the host immune response to viral infection, as NAD-dependent enzymes like PARPs (Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases) are involved in DNA repair and immune signaling [61]. This can indirectly influence the ability of the host to control HBV infection. It’s important to note that the specific mechanisms by which SIRT2 and NAD impact HBV replication are likely to be complex and may involve interactions with various host factors and viral proteins. Beyond aging and antiviral defense, they influence metabolism, circadian rhythms, inflammation, and stress responses. They also interact with a network of proteins and molecules, orchestrating a balanced cellular environment that promotes longevity and well-being.

The interconnected signaling systems involving NAD+ and Sirtuins are not just fascinating scientific phenomena; they are critical players in the grand narrative of human health and longevity. These intricate partnerships hold the promise of unveiling the secrets of aging, fortifying our defenses against viral threats, and promoting holistic well-being. Understanding the roles of NAD+ in these processes underscores its significance as a central regulator of cellular and human health, paving the way for innovative interventions and improved quality of life.

- Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinamide riboside, a new vitamin B3, and the emerging therapeutic potential of NAD+. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:115–130. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.107.120758

- Young SN. Acute tryptophan depletion in humans: a review of theoretical, practical and ethical aspects. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38(5):294–305. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.120209

- Richard DM, Dawes MA, Mathias CW, Acheson A, Hill-Kapturczak N, Dougherty DM. L-Tryptophan: basic metabolic functions, behavioral research, and therapeutic indications. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2009;2:45–60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4137/ijtr.s2129

- Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA, Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Macronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2005.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central (food composition database). Beltsville (MD): USDA; 2019–2026. Available from: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/

- Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJY, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, et al. Declining NAD+ induces a pseudohypoxic state, disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013;155(7):1624–1638. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037

- Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CCS, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, et al. CD38 dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an SIRT3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1127–1139. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006

- Grant R, Berg J, Mestayer R, Yoon U, Choe Y, Cheon BK, et al. A pilot study of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:147. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00147

- Houtkooper RH, Cantó C, Wanders RJA, Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):194–223. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2009-0026

- Trammell SAJ, Schmidt MS, Weidemann BJ, Redpath P, Jaksch F, Dellinger RW, et al. Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12948. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12948

- Hirst J. Mitochondrial complex I. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:551–575. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-070511-103700

- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Gatto GJ, Stryer L. Biochemistry. 9th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman; 2019. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/(S(ny23rubfvg45z345vbrepxrl))/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3401883

- D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribose )ylation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 2):249–268. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10455009/

- Chini CCS, Tarragó MG, Chini EN. de Oliveira GC, van Schooten W. The pharmacology of CD38/NADase: an emerging target in cancer and diseases of aging. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39(4):424–436. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2018.02.001

- Zakhari S. Overview: How is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(4):245–254. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17718403/

- Cantó C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: a balancing act. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):31–53. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023

- Yoshino J, Baur JA, Imai SI. NAD+ Intermediates: The Biology and Therapeutic Potential of NMN and NR. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):513-528. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.002

- Zakhari S, Li TK. Determinants of alcohol use and abuse: impact of quantity and frequency patterns on liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46(6):2032–2039. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22010

- Berthoud VM, Beyer EC. Oxidative stress, lens gap junctions, and cataracts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(2):339–353. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2008.2119

- Sies H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015;4:180–183. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.002

- Truscott RJW. Age-related nuclear cataract—oxidation is the key. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80(5):709–725. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2004.12.007

- Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CM, Klein R, Cheng CY, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106–e116. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(13)70145-1

- Williams PA, Harder JM, Foxworth NE, Cochran KE, Philip VM, Porciatti V, et al. Vitamin B3 modulates mitochondrial vulnerability and prevents glaucoma in aged mice. Science. 2017;355(6326):756–760. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal0092

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417–1436. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417

- Novak EA, Liu H, Chen J, et al. Nicotinamide riboside protects against experimental colitis and improves gut barrier function. Front Immunol. 2023;14.

- Peluso I, Villano DV. NAD metabolism links gut microbiota to host inflammation and barrier function. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2023;9.

- Niño-Narvión V, Rojo-López MI, Martinez-Santos P, Rossell J, Ruiz-Alcaraz AJ, Alonso N, et al. NAD+ precursors and intestinal inflammation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nutrients. 2023;15: (article number used by journal). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132992

- Lu H, Zhu X, Zhang H, Chi X, Liang X, Zhang Y. et al. SIRT2 and neuroinflammation: roles in ischemic stroke and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14.

- Dizdar N, Granérus AK. Intravenous NADH in Parkinson’s disease: a clinical study. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90.

- Birkmayer JG, Vrecko C. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) in the therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1989;101: (journal pages). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2644889/

- Rutherford E. Intravenous NAD+ therapy: safety, tolerability, and clinical considerations. (Clinical review/position article; journal uses article identifiers).

- Poyan Mehr A, Tran MT, Ralto KM, Leaf DE, Washco V, Messmer J, et al. De novo NAD+ biosynthetic impairment in acute kidney injury in humans. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1351–1359. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0138-z

- Ralto KM, Parikh SM. NAD+ homeostasis in renal health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(2):99–111. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0216-6

- Abdellatif M, Sedej S, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Autophagy in cardiovascular aging. Circulation. 2021;144(21):1713–1726. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.118.312208

- Brown KD, Maqsood S, Huang JY, Pan Y, Harkcom W, Li W, et al. Activation of SIRT3 by the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside protects from noise-induced hearing loss. Cell Metab. 2014;20(6):1059–1068. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.003

- Imai SI, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(8):464–471. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2014.04.002

- Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):225–238. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3293

- Xie N, Zhang L, Gao W, Huang C, Huber PE, Zhou X et al. NAD+ metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):227. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-020-00311-7

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16(4):667–685. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3484320/

- Draelos ZD, Jacobson EL, Kim H, Kim M, Jacobson MK. et al. A pilot study evaluating the efficacy of a topical preparation containing niacin derivatives in female pattern hair loss. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31: 258-261. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-2165.2005.00201.x

- Choi YH. Niacinamide down-regulates DKK-1 and protects hair follicle cells from oxidative stress-associated senescence. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22.

- Korcz E, Varga L. Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: Techno-functional application in the food industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;110:375-384. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.014

- Korcz E, Varga L, Kerényi Z. Relationship between total cell counts and exopolysaccharide production of Streptococcus thermophilus T9 in reconstituted skim milk. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 2021;148:111775. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111775

- Kapcsándi V, Hanczné Lakatos E, Sik B, Linka LA, Székelyhidi R. Antioxidant and polyphenol content of different grape seed cultivars and the possible use of grape seed flour in functional bakery products. Chem Pap. 2022;76(3):1279-1289. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-021-01754-0

- Kapcsándi V, Hanczné Lakatos E, Sik B, Linka LA, Székelyhidi R. Impact of tincture production on total polyphenol, total antioxidant, and total flavonoid content of some medicinal plants. Chem Pap. 2022;76(3):1323-1333. doi:10.1007/s11696-021-01755-z.

- Kapcsándi V, Hanczné Lakatos E, Sik B, Linka LA, Székelyhidi R. Characterization of fatty acid, antioxidant, and polyphenol content of grape seed oil from different Vitis vinifera L. varieties. OCL. 2021;28:30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1051/ocl/2021017

- Polgár B, Bódis J. Early pathways, biomarkers, and subclasses of preeclampsia. Placenta. 2022;121:166-173. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2022.03.009.

- Buzás H, Székelyhidi R, Szafner G, Szabó K, Süle J, Bukovics S, et al. Developed a rapid and simple RP-HPLC method for the simultaneous separation and quantification of bovine milk protein fractions and their genetic variants. Anal Biochem. 2022;655:114939. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2022.114939

- Nagy E. Mortality on DOACs versus on vitamin K antagonists in atrial fibrillation: analysis of the Hungarian Health Insurance Fund database. Clin Ther. 2023;45(5):598-608. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.03.008.

- Kovács B. A large sample cross-sectional study on mental health challenges among adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: at-risk group for loneliness and hopelessness. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:24-34. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.067.

- Orosz E. High prevalence of burnout among midwives in Hungary: results of a national representative survey. Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e24495. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24495.

- Fodor S. Peer education program to improve fluid consumption in primary schools: lessons learned from an innovative pilot study. Heliyon. 2024;10(5):e26769. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26769.

- Ráthonyi O. Pregnancy-induced gait alterations: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1506002. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1506002.

- Koh Y, et al. Long-term clinical and angiographic outcome of T- or Y-stent-assisted coiling of basilar tip aneurysms. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(12):2291-2298. doi:10.1080/14796678.2024.2435205.

- Uzzoli A. Innovative decision-making methods in medical fields: an analysis of multi-fuzzy sets and methods. Sci Rep. 2024;14:30137. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-79725-0.

- Moutia T, Lakatos E, Kovács AJ. Impact of dehydration techniques on nutritional, physicochemical, antioxidant, and microbial profiles of dried mushrooms: a systematic review. Foods. 2024;13(20):3245. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13203245

- Sami A, Javed A, Ozsahin DU, Ozsahin I, Muhammad K, Waheed Y. Genetics of diabetes and its complications: a comprehensive review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2025;17(1):185. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-025-01748-y

- Szatmári I, Santer FR, Kunz Y, van Creij NCH, Tymoszuk P, Klinglmair G, et al. Biological and therapeutic implications of sex hormone-related gene clustering in testicular cancer. Basic Clin Androl. 2025;35:9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-025-00254-5

- Uppal R, Saeed U, Tahir R, Uppal MR, Khan AA, Rahman C, et al. Lymphopenia as a diagnostic biomarker in clinical COVID-19: insights from a comprehensive study on SARS-CoV-2 variants. Braz J Biol. 2025;85:e284362. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.284362

- Uppal R, Rehan Uppal M, Tahir R, Saeed U, Khan AA, Uppal MS, et al. Bacterial infections and antimicrobial resistance patterns: a comprehensive analysis of health dynamics across regions in Pakistan (2013–2023). Braz J Biol. 2025;85:e285605. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.285605

- Westmattelmann D, Sprenger M, Lanfer J, Stoffers B, Petróczi A. The impact of sample retention and further analysis on doping behavior and detection: evidence from agent-based simulations. Front Sports Act Living. 2025;7:1578929. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2025.1578929